1,2-Dibromoethane: A Commentary on Its Past, Present, and Future

Historical Development

Back in the early 20th century, the push for improved fuels led scientists to try all sorts of additives. Through quite a bit of trial and error, 1,2-dibromoethane (sometimes called EDB in older papers) found a spot in petroleum refining. The story really took off when it paired with tetraethyllead in gasoline, helping engines run smoother by cleaning out lead deposits. This move meant longer engine life, saving drivers from hefty repair bills. Industrial chemistry didn’t just stumble on EDB; persistent research and a need to clean up engine emissions shaped its rise. Chemical manufacturers scaled up production, driven by the ever-present demand for good fuel. That early hunger for better performance wound up shadowing the compound’s drawbacks, an error that’s still worth looking at today.

Product Overview

1,2-Dibromoethane stands out as a dense, colorless liquid that packs quite a punch. More than just a fuel additive, this compound quickly found roles in soil fumigation and as a solvent. Companies packaged it up for use in everything from pesticides to flame retardants. The chemical’s effectiveness made it almost essential for large-scale agriculture through the ‘50s and ‘60s. Its ability to act both as a cleaning agent in machinery and a pest killer underground spoke to its versatility. But that same versatility introduced health and environmental worries, many of which became impossible to ignore once farmers and refinery workers raised concerns about odd health problems and groundwater contamination.

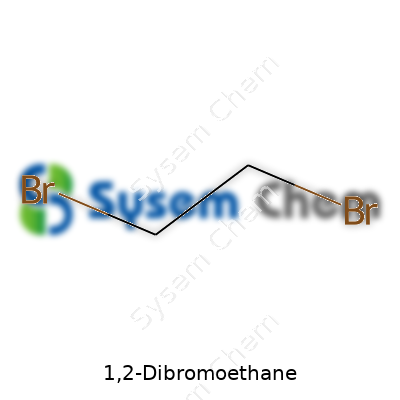

Physical & Chemical Properties

Anyone spending much time with 1,2-dibromoethane notices the sharp, sweet-ish smell before even glancing at a label. The compound shows up as a clear oily liquid. It weighs in at about 2.18 grams per cubic centimeter—a heavy hitter compared to water and most other solvents. It melts well below freezing at 9.5°C and doesn’t start boiling till 131°C, making it stick around in most normal conditions. It dissolves a bit in water, but not much, preferring to hang out with organic solvents. The bromine atoms attached to its short carbon chain make it highly reactive, which explains a lot of its practical uses and, frankly, its dangers.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Factories that produce or sell 1,2-dibromoethane must follow tight technical standards to avoid safety fiascoes. Labels call out its UN number (1605), and good sellers list purity ranges (usually above 98%) and specific gravities so users know what they’re getting. Safety data sheets should spell out all the recommended handling precautions—respirators, gloves, and detailed first aid steps. Sometimes small differences in labeling can cause real confusion on the shop floor, so regulators like OSHA and the EPA set clear guidelines. Without these, workers would face real risks—especially since even a small leak threatens both health and the surrounding environment.

Preparation Method

Industrial labs usually turn out 1,2-dibromoethane by passing ethylene through a cold solution of bromine. This direct addition grabs both bromine atoms onto the ethylene molecule, all in a controlled reaction that produces almost no side products. The process looks simple on paper, yet keeping it safe at scale takes real skill. Unreacted bromine and the exothermic heat mean you need solid engineering and careful monitoring. Companies have tinkered with continuous flow setups, upgrades in reactor design, and closed systems to cut down on worker exposure—all learned from accidents and near-misses that forced better solutions.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The bromine atoms sitting on 1,2-dibromoethane turn it into a prime target for nucleophilic substitution. In practice, this means the compound acts as a useful synthetic building block, handing over its bromine atoms to make new chemicals that feed into pharmaceuticals, dyes, and specialty plastics. Scientists have found many ways to tweak the molecule, swapping out functional groups and building bigger chemicals from this small two-carbon chain. In the lab, 1,2-dibromoethane helps make Grignard reagents and other organometallic compounds, hopping right into reaction schemes dreamed up by chemists in academia and industry.

Synonyms & Product Names

People in the chemical trade often call this compound ethylene dibromide, or simply EDB. Over the years, manufacturers packaged it under a string of names—Bromoethane, Glycol dibromide, and even some branded agri-chemical titles like Dowfume and Soilbrom. Old catalogs and regulatory lists may use entirely different monikers, which gets confusing for anyone tracking international shipments or reading older research articles. Synonyms help connect the dots between different applications and rules for safe use, and ignoring those variations can mean missing some key warnings or restrictions.

Safety & Operational Standards

This compound has a nasty side. Inhaling the vapors or splashing it on skin leaves workers at risk for nausea, headaches, lung injury, and even cancer with enough exposure. Safety protocols really matter. Personal protective gear, proper ventilation, and regular monitoring for leaks keep exposures down in factories. Federal regulators stepped up requirements after a run of poisoning cases and discoveries of EDB in groundwater. Distribution tightly controls sales now, and disposal methods come under strict review to avoid environmental spills. Having worked in labs alongside seasoned industrial chemists, I’ve seen how seriously they take accident prevention. No lab coat or safety goggles gets skipped just because you’re “only moving a little bit.”

Application Area

1,2-Dibromoethane has worn several hats: originally a staple in leaded gasoline to break down gunky engine deposits, later as a soil fumigant to wipe out nematodes, and at one point as a mothproofing agent. Its declining use traces back to discovery of its hazardous health impacts and the phasing out of leaded gasoline. Even so, it lives on in small way in chemical synthesis, sometimes helping build other compounds in the pharmaceutical and plastics industries. Many farmers, mechanics, and chemists once relied on it, recognizing its power and, in time, its dangers.

Research & Development

Early research homed in on how EDB could improve fuel performance and root out tough pests. Over time, environmental scientists began digging deeper, poking holes in its safety profile. Toxicologists mapped out pathways in the human body, showing how it could mess with organs and genes at tiny doses. Modern R&D efforts now focus on finding safer substitutes and breaking down EDB left in soils and water. Students and postdocs have churned out plenty of studies on remediation, from microbes tuned to digest the compound to advanced water filtration. Each research cycle uncovers another unintended side effect, which keeps the scientific community hustling for better answers.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity studies painted a bleak picture. Short term, exposure burns the eyes, nose, and lungs. Over a career, the risk ramps up for reproductive issues, liver and kidney damage, and higher rates of certain cancers. The EPA now lists the compound as a probable human carcinogen. Real people—farmworkers, mechanics, chemical plant workers—have borne the brunt of these risks. Years back, I watched old-timers urge new hires to double up on gloves or “never trust a closed bottle.” That advice comes from grim experience, and case studies now back them up. Ongoing animal studies keep adding details about subtle impacts, including DNA damage and hormone disruptions, making it hard to argue for any widespread return to old-style usage.

Future Prospects

Most new industries steer clear of 1,2-dibromoethane, especially as consumer safety groups stay vocal about past mishaps. Remediation companies build tech to dig EDB out of contaminated soils. Some chemists use it for tightly controlled lab reactions when no good substitutes work. Tomorrow’s answers may come from green chemistry, pulling safer, bio-based alternatives into old EDB roles. Governments worldwide cling to strict bans and reporting rules, with some exceptions for states dealing with legacy fuel or agricultural pollution. Research on breaking down leftover contamination—using sunlight, smart microbes, or advanced materials—holds the best hope for cleaning up the messes left behind and for shaping safer chemical management across the board.

The Role in Leaded Gasoline

1,2-Dibromoethane, better known by old-timers in farming and car culture as ethylene dibromide, mostly made headlines once as a lead gasoline additive. Adding this chemical to leaded fuel once helped car engines stay clean by making leaded deposits less sticky and easier to flush out. Engines back then ran smoother, avoiding buildup and clogged valves. Leaded gasoline has faded to the sidelines for good reasons, but the legacy of 1,2-dibromoethane in this setting reminds us how chemistry and policy often dance together.

Pesticide and Soil Treatment

This compound gained widespread use as a fumigant for crops and soils. Farmers turned to it to fight insects and nematodes lurking in fields, especially in agriculture-intensive places growing vegetables, grains, or tropical fruits. The harsh truth—1,2-dibromoethane is toxic—helped contain aggressive pests but also raised eyebrows about long-term health risks, including cancer and groundwater contamination. Disease-free harvests looked inviting, but too many applications left residues all through the food chain. After enough evidence built up showing risks weren’t just theoretical, regulators in many countries clamped down and pulled its registration for food crops.

Industrial and Laboratory Reactions

Chemists and material scientists see 1,2-dibromoethane as a handy source of bromine in the lab. Its structure, with two bromine atoms, brings out reactions for making other chemicals. It shows up in the production of dyes, pharmaceuticals, waxes, and cleaners. Its role as a chemical intermediate—basically, a go-between step for new molecules—matters most in research and manufacturing. People with experience in a chemistry lab know the sharp odor and handle it with care, usually under a hood, because airborne vapors burn the eyes and lungs fast.

Cleaning and Degreasing

Some factories, especially in electronics or metalwork, used 1,2-dibromoethane in mixtures as a solvent. Oils, fats, and waxy grime don’t stand much chance against its cleaning power. In the past, I saw old manuals recommending it for cleaning electrical parts. Nobody wants sticky switches or contacts in crucial circuits. Over time, the environmental and worker safety concerns far outweighed the convenience, which drove a shift toward safer alternatives.

Storage and Quarantine Fumigant

1,2-dibromoethane played a strong role at ports and in warehouses. Its use as a fumigant for quarantine—especially for logs, seeds, and imported plant products—protected against invasive insects and pathogens. Infestations cost societies big if left unchecked. Yet, the residual contamination turned out heavy. After seeing both worker and environmental health at risk, many countries phased out or banned its use in quarantine operations.

Public Health, Environment, and Future Approaches

Experience proves that 1,2-dibromoethane saves money and yield but brings long-term costs nobody wants to inherit. It lingers in soil and water, harming wildlife and people. The United States Environmental Protection Agency, along with the World Health Organization, flagged it as a probable human carcinogen, no longer suitable for general use. Alternatives—either natural or less persistent chemicals—offer a safer path. Pushing for integrated pest management and strict industrial protocols gives us a chance to enjoy progress in science without trading away public health and the land itself.

Getting Real About Risks

Working with 1,2-dibromoethane isn’t a casual, everyday task. Anyone who has been in a chemical lab or agricultural supply site knows the smell of something “off” before they see the hazard label. Years back, I watched a neighbor in ag-research scramble after a cousin splashed a little bit on a work shirt. Nobody fell ill that day, but it proved how quickly things change if you slip up. This compound once filled fumigation tanks and gasoline blends, but it’s found less and less because of the risks. Human error and a moment without proper gear cause real problems long after the shift ends.

Why 1,2-Dibromoethane Demands Respect

This stuff punches above its weight. Breathing in the vapors causes sore throats, coughing, and head spins, even at levels you might barely notice. Eye contact brings stinging and blurred vision. Soaked through the skin, exposure makes hands itch, rash up, or even blister, and the body absorbs it way too fast for comfort. Data from the CDC calls out its cancer hazard and impact on nerves and lungs. Material safety documents drill home: tiny doses over months can damage organs. This isn’t just a white-coat issue. Farmers, warehouse crews, and mechanics can all run into it.

Simple Steps Protect People

Safety starts before even opening the bottle. Anyone using this chemical should have nitrile gloves, chemical goggles, and a face shield. Cotton gloves don’t block the stuff; lessons get expensive. Always suit up with a proper lab coat that doesn’t let much through. I stick with lab partners who believe in sturdy rules, not shortcuts. Closed-toed leather or rubber shoes save toes and the soft parts around the ankles, which absorb chemicals in a flash.

Don’t trust cheap dust masks. Only use respirators meant for organic vapors. These can take getting used to, but they beat a cough or a worse call later. Small fans do not move clouds of vapors away from your face. Use a ventilated hood—if I don’t see the sash down and the air moving hard, I wait.

Make a Plan for Spills and Storage

I learned fast that every container needs secondary protection—trays or bins—to catch leaks and drips, since a stain on a bench can linger. Never leave this bottle near food, pipes, or breaks in the work zone. Label everything, even the rinsed glassware. Colleagues get sloppy in a rush and mistakes happen quickly. If a spill happens, cover it with absorbent pads designed for chemicals, then scoop it up with tools—not bare hands. Hazard bins, not the trash. Wash skin fast with soap and water, get goggles rinsed in minutes, and dial up medical backup early—it isn’t overreacting.

Store 1,2-dibromoethane locked down, away from sunlight and heat. I like cabinets with metal locks and clear warnings in front; out of sight leads to forgetfulness, which never ends well. Keep only what you need on hand for the job—excess means extra worry.

Better Habits Mean Fewer Worries

Nobody enjoys paperwork, but keeping training fresh and practicing with mock drills makes a huge difference. Many workplaces roll eyes at scheduled reviews, but every close call leaves a story worth listening to. Government reports and OSHA stats repeat one lesson: planning wins. The trust built by treating these chemicals with care spreads through the whole site. By taking simple, proven steps, nobody has to carry the regret and stress that come with a careless mistake.

Getting to Know the Basics of 1,2-Dibromoethane

1,2-Dibromoethane, sometimes called ethylene dibromide, stands out because of its structure: two bromine atoms linked to a simple two-carbon chain. People who study or handle chemicals will notice a sweet smell when opening a bottle, and its oily, clear liquid form looks harmless. That kind of appearance has fooled many before, but this is one tough molecule. It evaporates more slowly than water, so spills take time to dry up. The colorless nature hides its punch, but small drips can cause trouble—both for people and the planet.

Physical Properties That Command Attention

In any chemistry lab, 1,2-dibromoethane draws interest. It boils at about 131°C, which means fire or high heat makes it turn to vapor. Its melting point sits around 9°C, so in a cool fridge, it goes solid. Pour it into water, and it sinks—it’s denser (2.18 g/cm³) and hates mixing with water. Instead, it floats on oils or other organics. This separation defines how it moves in soil or spills: hefty and persistent, it refuses to disappear.

If dropped at room temperature, the air quickly fills with its vapor. Its vapor pressure runs at 11.5 mmHg at 25°C, which sounds technical, but think of it as a sign that it wants to be in the air and not the bottle. Take a sniff, and it delivers strong fumes. Safety gear always matters with 1,2-dibromoethane—run the vent, wear gloves, and never breathe it in on a dare.

Chemical Behavior and Why It Matters

The real issue with 1,2-dibromoethane lies in its chemical punch. Bromine atoms on an ethylene backbone create a molecule ready to react. Under the right spark, it supports combustion, releasing hydrogen bromide—a corrosive, dangerous gas. In water (even just humidity in the air), it breaks down slowly, giving off more brominated byproducts. Once, farmers used it as a pesticide to kill bugs in soil, but its ability to seep through groundwater and stick around for years raised alarms. Studies show it’s a probable carcinogen for humans. It can damage organs, especially the liver and kidneys, after repeated exposure.

In an industrial setting, 1,2-dibromoethane acts as a lead scavenger in fuel, a chemical intermediate, or a fumigant. Regulations now restrict its use. Ecology research highlights that this chemical drifts far from its origin. Soils and streams become tainted, wildlife suffers, and tap water turns risky. Testing labs check wells and food grown near leaking tanks.

Solutions and Personal Responsibility

Anyone storing or using 1,2-dibromoethane can’t afford shortcuts. Proper labeling, secondary containment, and regular leak checks make accidents less likely. Full transparency builds trust—neighbors deserve to know what’s in the soil and air. Emergency teams need clear training about how to react fast if there’s a spill. Firms owe it to their workers to provide adequate safety gear and up-to-date disposal information. Regulators should keep up with new science, making stricter rules when health or water supplies are at stake.

Push for green substitutes remains a smart move. Chemistry teachers can show how carefully crafted molecules can achieve the same job with fewer health risks. Parents, workers, and local communities have a voice here. Press for accountability but also celebrate the advances that make old chemicals like 1,2-dibromoethane less central to daily products. Awareness leads to protection—environmental health and safe workspaces benefit everyone in the end.

Health Risks Lurking Behind a Widely Used Chemical

1,2-Dibromoethane often shows up in places many folks never expect: gasoline additives, soil fumigants, and even some historical pesticides meant to protect crops. The problem is that this chemical, also called ethylene dibromide, packs far more danger than meets the eye. You can't always see or smell it, but that doesn't mean you're safe around it.

Research has linked exposure to 1,2-dibromoethane with several health problems. Inhalation or skin contact can trigger everything from skin irritation to serious problems with the liver, kidneys, or respiratory tract. Long-term exposure raises the stakes, connecting this chemical to cancer risks, especially cancers of the stomach and lungs. Back in the 1970s, people working with it in leaded gasoline experienced increased rates of respiratory illness and even nervous system issues. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has classified it as a probable human carcinogen, not just based on animal studies but also on cases involving workers.

Environmental Fallout That Travels Far and Lingers

Spills or leaks do not stay local for long. 1,2-Dibromoethane can seep into groundwater and stay there for years. Even small amounts in the soil make their way into crops and water supplies. The chemical is persistent, resisting breakdown by sunlight or bacteria in many conditions. Communities rely on groundwater for drinking and irrigation, so contamination puts many at risk for health issues and loss of safe water.

Once, farmers relied on this chemical to kill pests in soil. The harm done to groundwater and wildlife led many countries to place bans or severe limits on its use. Fish and aquatic organisms are especially vulnerable. Studies show that waterborne concentrations, even just a few parts per billion, can disrupt reproduction in fish populations and harm amphibians.

Industry Practices and the Importance of Accountability

Factories and refineries using 1,2-dibromoethane have often argued that proper handling and regulation reduce risks. That sounds nice in theory, but spills or improper disposal still happen. My community once grappled with concerns over contaminated well water near an old industrial site. People worried for years about the possible cancer cluster until cleanup efforts finally took root. Stories like this pop up across the country where oversight slipped or monitoring failed.

Urban and agricultural workers face elevated risks, especially in regions where older storage tanks or outdated equipment are common. Regulations require ongoing testing and protective equipment, but enforcement costs money, and shortcuts get taken more often than most admit. Workers deserve better—nothing justifies risking someone’s life for a shortcut. Greater transparency and real investment in safer alternatives would protect workers and communities.

Steps Toward Safer Living

Some states demand regular groundwater sampling for certain chemicals, but others lag behind. National standards for cleanup should be the rule, not the exception. Companies working with hazardous chemicals must give local communities accurate, honest information. Stronger penalties for illegal disposal—and real support for victims—can motivate better behavior.

Finding safer pest-control methods and industrial additives will take time, but sticking with a toxic status quo is not the answer. Support for research into replacements will pay off for the health of people and the planet. Clean water, safe air, and healthy soil never come from taking chemical shortcuts.

A Closer Look at 1,2-Dibromoethane

1,2-Dibromoethane, known in some circles as ethylene dibromide, has found a place in agriculture and industry. People use it to fumigate soils, treat wood, and even in making leaded gasoline. Experiences with chemical storage have shown me a single oversight can snowball into bigger problems—both for health and for the environment. Since this clear, heavy liquid carries significant toxicity and can even cause cancer, those handling it can’t afford shortcuts.

Keeping 1,2-Dibromoethane Secured

Storing hazardous chemicals doesn’t just mean shelving a bottle in a closet. 1,2-Dibromoethane needs a steel drum or tight, corrosion-resistant container. Store it in a cool, well-ventilated area, away from direct sunlight or heat sources. Some warehouses use explosion-proof refrigerators or cabinets that resist chemicals like acetone or bromine, since a leak can eat through ordinary plastic.

Experience tells me not to keep incompatible chemicals together. Strong oxidizers, acids, and alkalis mix badly with 1,2-Dibromoethane. I’ve seen labels fade and caps corrode, so double-checking containers for damage keeps everyone safer. Ventilation matters because fumes pack a punch and can provoke coughing, dizziness, or much worse, especially over time. Good practice involves containing spills instantly, placing suitable spill kits close to where chemicals get used or stored.

Disposal Calls for Precision

Once 1,2-Dibromoethane gets past its shelf life or someone wants it gone, tossing it in the trash or pouring it down a drain isn’t responsible. It could seep into groundwater or poison wildlife. EPA classifies this chemical as hazardous waste, which means handlers need a licensed waste management contractor. I’ve watched people try shortcuts with chemicals—these choices seldom end well and can prompt fines or jail time.

Handing off waste safely starts with labeling containers clearly, using compatible materials that won’t leak. Letting untrained staff try to neutralize chemicals rarely saves money, and may scatter contamination farther. Some facilities use high-temperature incinerators designed for halogenated waste. Burning it wrong or sending it to a landfill means trouble: toxic breakdown products like bromine gas or dioxins are far worse than the original chemical.

What Moves the Needle Forward?

Training makes the biggest difference. Teams who take yearly updates about new regulations or safer methods catch mistakes before they happen. Wearing gloves, splash-proof goggles, and respirators looks awkward, but these layers work. I’ve toured sites where safety became routine, not a box-ticking chore, and nobody cut corners—incident rates dropped overnight.

Digital tools play a role, too. Real-time inventory management alerts teams before chemicals expire or reach critical stock. Automated systems reduce human error, shutting off HVAC in an emergency or locking down storage if sensors detect leakage.

Responsible Handling Protects More Than Workers

Following these guidelines shields communities, workers, and the land beneath our feet. 1,2-Dibromoethane demands respect not only for its strength, but for the legacy it leaves when mismanaged. By approaching it with careful planning, personal protective equipment, and professional disposal, its risks can be kept in check. Better storage and disposal improve everyone’s peace of mind and public health.